Last month I was honored to be a guest on Kyle Smith’s The Growing Band Director Podcast – a highlight of my Summer. After our time together he decided to call the episode, “Teaching Analytically“. I’m really proud of that, because it connects to the fundamental goal of my choral program: to develop our students into analytical musicians. The degree to which I succeed or fail at that can always be open for debate, but that is my reason for being at York High School. Music literacy takes many shapes and forms, but each of them requires one to be analytical. Along those lines, Kyle and I only touched briefly on assessment practices in the music classroom, but it’s something I feel compelled to elaborate on as we begin a new school year.

Assessment is not only a core component of my program, I believe it has never been more critical for the profession to embrace assessment practices as core as well. I think I can break the reasons down into a few categories:

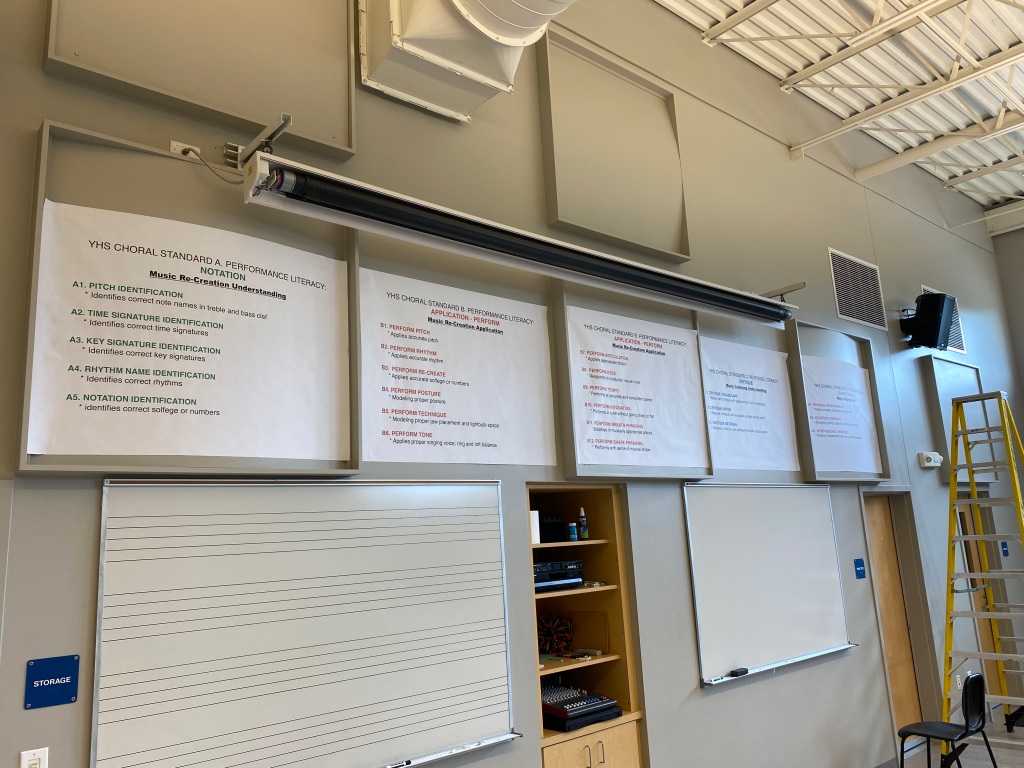

BUILDING BLOCKS – It is way too easy in the music classroom to focus on what our students are singing/playing for literature. But it’s been amazing over the years to have deeper conversations with colleagues around this very point. When students are working on their music, what are they learning; what are they developing? Both, “the music” and “their musical skills” are throw away answers that undermine our obligation to the profession and to our kids. If we are here to educate and develop musicians, then the literature must be an extension of very specific learning targets. We know they develop skills, but which ones? How do they overlap and inform each other? When do we address them specifically vs. parenthetically, and do our students understand the specific skills they are to be developing in our classroom on any given day? The building blocks of our music classrooms must be chewable, digestible and transparent. This is why I went standards based 13 years ago, and why I can’t imagine being a music teacher without them. But I don’t assess standards, I assess the sub-particles: indicators. These are my learning targets. My students know them, my students understand which ones we are focusing on at any given moment, and those are what my students are assessed on. By having assessment at the heart of my classroom, I am required to articulate these building blocks in a way that requires me to be…. wait for it…. analytical about why and how I do what I do. The beneficiaries are the students.

FEEDBACK LOOP – This practice is an essential process for student growth in any academic subject, but I would argue especially so in the performing arts. If I have established learning targets for my kids, then providing a process for them to grow is absolutely critical. When you incorporate feedback loops as a foundational component of your program, you open up a whole different world of music education. Assessment is so much more than how a student did. Last Fall I met online with Senior music education majors at UMaine to talk about standards and assessment. I mentioned that my students are held accountable in part by having a unique indictor of “meeting deadlines” attached to each assessment event that mathematically factors into their grade. One of the Seniors respectfully but vehemently pushed back by saying, “… that’s the same as just giving a homework grade with points taken off for being turned in late.” Gradewise, it looks the same. But in a feedback loop, it is never about the grade: it’s about the feedback. If I give a student a “B” on their video assessment which I gave for homework, that provides nothing more than a percentage. If on the other hand I give them 5 independent and specific indicator scores: “3” for tone, “4” for jaw placement, “2” for diction, “4” for pitch accuracy, and perhaps a “1” for meets deadlines, then I have fed the feedback loop which informs my individual students, allowing them to take that feedback and run with it.

PROFESSIONAL GROWTH – By definition, to develop analytical musicians, your students must model your analysis of their skills and growth. They a) do not know your analysis unless you provide it, and b) cannot do anything about it on their end without it. There is no way – no way – you can engage in this analysis without growing as a professional. When I formed my first set of standards and indicators thirteen years ago, they were based loosely on the Maine Learning Results and National Standards. But I say “loosely” because neither one was as applicable, transparent and relevant to my students as I felt they needed to be. If that sounds like a slam on them it’s not: I was one of the writers for the Maine Learning Results. But neither a state nor national document can meet you specifically where you are at in your program. What I had to decide was how to create a functional set of indicators, organized in a fashion that made sense to my students and their parents. I also needed every indicator to be somewhat the same grain size. Coming up with these learning targets for York High School music students was one of the best professional development experiences I’ve ever had. It wasn’t a hoop to jump through, and it wasn’t a document to complete and put on a shelf: it would be a living guideline, informing my every day instruction. Coming up with these standards and indicators caused me to reflect and grow in some profound ways as an educator. Since that Summer of 2011, I have revised these at least seven times, each instance being because I wasn’t satisfied with them. Developing them forces me to be analytical, and there isn’t a greater impetus for professional growth than that.

TECHNOLOGY CAUGHT UP – This is less a reason for embracing assessment as a foundational cornerstone of your program, than it is an acknowledgement that now there’s really no excuse not to. When Smartmusic launched it’s first major update to include real time feedback on pitch accuracy in the mid 2000’s, I took it, assigned all my students as instruments, and started using it on them. It was crude, but it was a start. It was also all I had. Now we live in a comparatively technological utopia. I can digitally gather data from my students and use technology to provide feedback for the feedback loop. Every other week my choirs are assigned a video assessment which they perform from home. They record themselves on a phone or computer, submit the video or recording directly into our school platform (google classroom for York), and then I can type and/or voice record feedback directly into that platform as well, easily transferable to our grading platform (powerschool). It could not possibly be easier or more seamless. One of the things Kyle mentioned during the podcast is that one of the reasons individual student assessment scares off music teachers is the perception that it takes a lot of, or extra, time. My messaging for over a decade has been: make it manageable. You can assess a half dozen indicators with a 60 second recording. But you can also assess just 1 or 2 indicators if you want in a 15 second video/recording. You can provide written feedback, or in the case of google classroom you can provide audio feedback through Mote. I can blow through fifty video assessments in an hour or really dive deep if I have the time and do it over a couple of hours. Want to get real feedback in real time? Have them sit/stand a bit farther apart during rehearsal and have them record a sight reading, or an excerpt from a song, or a warmup that you use to develop a very specific skill. Game on, took no addition time on your part or theirs to create. But you still get your data. My point is simple: make it manageable. Technology has caught up with our needs. Anyone wanting to speak with me more about this can feel free to e-mail me at rwesterberg@yorkschools.org and I would LOVE to provide resources and point you in a direction that works for you!

ADVOCACY – The double edged sword of administrators (or parents, community members, school committees, etc) who don’t know much about what we do is self evident. I have met music teachers over the years who gloat over the fact that their administration lets them do what they want, and often times their messaging is, “just so long as the kids are engaged and having fun.” To me that’s a slap in the face because I guarantee you they aren’t giving the same message to their math or science teachers. English and science? How are the students doing academically? Wanna know why music has been on district chopping blocks for decades? Music students are not expected to be held academically accountable. Change that. Want to argue that your students are already learning and growing and you don’t need to adopt rigorous, transparent assessment practices to accommodate or prove that? I was the drama club director for our musicals at various points at all three schools I’ve taught at. I was also music director for them, but being the actual director is more closely aligned with what I do in the classroom as a teacher and I loved doing it. I took great pride in my students’ education through the experience, and can tell dozens of stories of their personal and musical growth. These are still some of my favorite educational experiences of my entire career. AT NO TIME DID I EVER FORMALLY ASSESS THEM. Wanna know why? They were educational in nature, not academic in nature. I came across a great quote articulating the distinction: “Education is gathering all the knowledge by various means like reading, experiencing, studying, travelling, listening etc. In academics, you are provided with a structure by following which one will gain the theoretical knowledge and sometimes practical.” Does your community view you as educational or as academic? Be really careful with your answer. What are you doing – or not doing – to feed their perception? If your music classes meet outside of the school day or are overtly clubs or extra-curriculars, awesome. But if they meet during the school day and you receive the same continuing professional contract as teachers in the other subject areas, you had better be perceived as academic, holding students academically accountable. Question: what are you doing about it, and can adopting assessment practices aligned with learning targets and measured student growth further the cause, both of your program and of our profession?

During the podcast, I heard myself say that I love teaching more than I love music. I haven’t always known that, but I do now, and I don’t think I’ve often articulated it. My assessment practices are far from perfect, and I’ve never claimed them to be. They continue to evolve. But I know that making them the cornerstone of my entire program has clarified my role as an educator, has fed my students, has fed me, caused me to discover new resources, and has informed the general public as to why what we do at York High School in music is essential. In the end, I am a better and happier music teacher with them than I could ever hope to be without them. One of Kyle’s mantras is a great quote, “If you’re green you grow, if you’re ripe you rot.” If you’re still green in the realm of assessment practices, I have good news for you: we all are, me included. I hope you will consider this a focal point for growth as you begin your new school year.